This blog accompanies the econ101ab Principles of Economics course given at the University of Birmingham. The lecturers for both parts of the course (101a, microeconomics and 101b, macroeconomics) will occasionally post here on matters related to lecture material. We hope to show the relevance of the concepts we are teaching at each stage of the course for helping understand how the world works...

Thursday, November 10, 2011

What's Happening in the Eurozone?!

Nonetheless, the world doesn't stop between March of one year and January of the next, and one vast, gaping example is the eurozone crisis.

What, exactly, is going on here? One thing that is hugely true is that anything surrounding Europe in any form attracts huge amounts of emotive and vitriolic argument, and not a little bit of deception too by those able to keep their emotions hidden. Europe may divide the Tory party, but it also divides most British folk too.

So we must try to abstract from this. What is currently happening is a number of countries within (and without - e.g. Iceland) the eurozone is that they are struggling to borrow to cover their spending plans. In all cases, governments have particular spending plans they would like to enact, and in order to fulfil them they are currently borrowing because tax receipts do not cover their desired expenditures. The problem is that such borrowing requires paying interest to the willing lender, and currently a lot of lenders appear to be less willing to lend to these countries.

In some cases, this has got to the stage where a default (the country effectively goes bankrupt, telling those that lent to it that they won't be repaid ever) seems inevitable. Naturally, the problem here then is for those creditors who lose a source of income, and also for the governments that default since it will lead to dramatically higher interest rates in the future to borrow (would you lend to someone who just told people they couldn't repay?).

There then appears to be a problem because some of these countries that may default are within the eurozone. Were these countries like the UK and outside the UK, then a default may be less likely because they could simply print more money to pay off debts and inflate away the debt in time, but of course this recourse isn't available to eurozone countries since they do not have the power to print their own currency. Also, outside the eurozone they could default, making them more competitive as a nation hence hopefully able to start exporting more and importing less which would help the process of escaping from debt. However, if their debt was denominated in a foreign country (e.g. US dollar or euro), then this devaluation would only make the situation worse, as their debts would increase.

It will probably be fairly obvious, but a large number of people are suggesting that the euro is entirely to blame for the problems countries like Spain, Italy, Ireland and Greece are suffering, because they can't devalue. But it's a little more complicated than that, since as said that assumes their debts are in their own currency. Many countries borrow from abroad, and were Greece outside the eurozone, it's not obvious they wouldn't still have borrowed from eurozone banks. When debt is denominated in foreign currencies, then if an economy runs into trouble as Greece has, and its currency depreciates as would be expected, then its debt increase because they are foreign currency debts.

Generally, those blaming the euro for all the troubles were predisposed against the euro, because as you are likely learning, things are never quite as simple as that in economics, and often a bit of economic theory spoils a good rant.

Now, what are the consequences of a eurozone country defaulting? Does it need to leave the eurozone as a result? It doesn't appear obvious that they do - although again, those that don't like the euro appear dead set on presenting this as the only outcome. Given the trans-national nature of the monetary system they are engaged in, Greece defaulting is little different to any economic entity (e.g. a firm, a person) going bankrupt within a country. They will suffer the consequences as they rebuild afterwards, and perhaps some functions of government activity in Greece will be disrupted for a while around the default. But they will recover.

Why, then, are eurozone countries (and the IMF and the EU) ploughing millions and billions and trillions into Greece? Probably the best explanation (that doesn't recourse to euroscepticism) is, like the bail out of the banks in 2008, governments see this as the course of action that minimises disruption. A full scale default by Greece would create some problems for banks that are exposed to Greek debt, which would then translate into the domestic activity of these banks, already criticised for their lack of domestic lending in many countries. The consequence would be, of course, more depressed economic activity.

However, it seems the result of such actions of ploughing in the trillions is only to prolong the agony as opposed to actually providing Greece with any lasting solution. Some kind of adjustment (it is an economy that doesn't produce productively enough, effectively) is required in Greece but the problem is that in the course of that adjustment things will only get worse - budget deficits worse, economic growth worse, etc. The bottom line though appears to be that the necessary adjustments don't appear to be being made because they are not being forced to be made because of all the talk of European bail outs, repeated ones, that just prolong the market uncertainty.

Greece simply defaulting of its own right, starting from scratch again, is likely the best solution. It won't be pretty, but most likely a lot prettier than the current situation of bail out after bail out being announced, none of which are ever sufficient to stem market uncertainty (nor should they be since Greece as an entity does not appear to have changed). The Greece starting from scratch could decide from the outset what its desired level of public spending and government intervention is, and could decide this based on what it can borrow and at what rates (potentially not even borrowing at all). Currently its previous obligations tie it (and the rest of Europe) up in knots; at least if it defaulted and started again, that uncertainty would be over.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Keynes, Economics and Econometrics

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

BAE Systems and Welcome!

Welcome to Birmingham! Term has just started in earnest, and if you've just arrived to start your first year here, a particular welcome! Come second term, after Christmas, you'll have me lecturing you on macroeconomics for econ101b, while currently you have Martin Jensen for econ101a, Principles of Microeconomics.

Both terms we'll be teaching the basics of economics and attempting to apply them to events happening in the world around us. One such event that is happening today is that BAE Systems is announcing the shedding of a large number of jobs. This is being billed as very bad news for the economy, and undoubtedly it is not great news since it is people losing jobs, losing incomes, at a not particularly bright time economically.

However, such a superficial analysis is bad, and has potentially troubling implications. The analysis is very short term in nature, and implies that perhaps governments should be doing more about things like this. It's short term because BAE is acting now to keep itself in good business shape moving towards the future - it will be more profitable as a result, and will exist longer into the future, providing jobs throughout the UK for longer.

It's also a partial analysis in that it considers just one firm in just one industry - and also makes the suggestion that we should be protecting this particular industry since it is a UK based exporter. But should we? You will learn (or be reminded) about perfect competition this term, notably the idea that in an ideal situation, firms will expand until all profit opportunities are exhausted, and also will exit markets for which profit opportunities have turned into loss-making enterprises. Clearly, in its current shape, BAE is not profitable, and if it is to be supported in that shape, it will become bloated and uncompetitive on a global stage - exactly what we apparently most want in the UK economy.

Instead, these skilled workers should be allowed to move to other companies or industries, allowing them to grow where there are profitable opportunities - and such growing industries will almost certainly export, and even if not, they will be producing what people want (since they are profitable).

There is no reason for government to get in the way of this and thankfully the signs are good. By not getting in the way will the government achieve this aim of "rebalancing" the economy - they will allow, if red tape is cut, businesses to grow in areas where there is demand, as opposed to offering tax breaks to any particular industry - such favourable treatment for any industry will only result in more of the same.

So: I hope you're looking forward to studying here at Birmingham and challenging your perceptions about real world events using the tools of economists. See you next term!

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

John Redwood and His Blue Tinted Glasses

A little too often I end up reading (and often) linking up to stuff written by US economists about the US economy. It often has a lot of relevance for the UK economy. I do now read a few UK economics blogs, and highly recommend some of them.

Towards the left of centre, and inherently sensible, is Duncan's Economics Blog. You may want to rule out the blog's writer, Duncan Weldon, because he was involved with advising the previous Labour government. I'd urge you to get past that, and remember that more often than not, politicians ignore the best advice of economists. Duncan is highly knowledgeable, and engages with those on both sides of the debates that rage within the discipline of economics. I'd recommend this perhaps most highly of the UK economics blogs I read - the only downside is that he doesn't post quite as frequently as some.

Another blog in the left-of-centre realm is Stumbling and Mumbling; while this guy (Chris Dillow) claims not to be an economist, he is very familiar with a lot of economics, and hence his blog is hugely interesting. In general its microeconomic, but it does step out into the macroeconomic, and this recent post on the 50p tax rate is, as usual, excellent. Of course, it should be pointed out, Dillow is a self-proclaimed Marxist.

Then, of course, there is the other side of the spectrum. There's David Smith's Economics Blog, written by a Sunday Times economics correspondent. Even if you are more persuaded by those who lean left, I'd strongly encourage you to be reading what those you disagree with say, and respond to it. That's one of the reasons I read these blogs. Smith is scathing at times about the previous government and the current opposition (I think unreasonably so), but is constructive in what he suggests, and his recent post on the possibility of future Quantitative Easing and other monetary measures is worth reading.

If you want to read someone that right wingers champion as a great economist, but who is actually a politician and hence anything he writes should be taken with a large pinch of salt, try out John Redwood (if you can get past that picture at the top!). Redwood is apparently a trained economist, yet he is clearly a politician first, economist second, if his recent post on immigration is anything to go by. You can try very hard, but you'll be hard pressed to find an economist who believes blocking immigration (particularly at some arbitrarily set cap) is a good thing, yet Redwood's constituents want this, and hence so does he, and he makes all sorts of contortions to justify why he opposes immigration. He is also unashamedly partisan, as this post about the banks shows. He can't resist a pop at the last government in his closing paragraph - choosing to ignore all the financial big bang legislation of the Conservatives in the 1980s and 1990s, instead trying in true politician style to lay all the blame for the size of the financial sector at Labour's door.

It's nonetheless good to read the blogs of people like Redwood, and if you're more of a right-wing disposition, Weldon and Dillow. You'll disagree with them undoubtedly, but it will help you greatly as you develop at university as an economist to think about why you disagree, and why you think they are wrong; are your arguments really up to scratch?

Monday, September 5, 2011

Keynes, Hayek and Economics

The new academic year is about to start, and hence you may be about to make the journey to Birmingham to begin your undergraduate degree in economics, and may have somehow stumbled across this blog - if so, welcome! If not, welcome still. The point of this blog is to help those studying econ101ab at Birmingham to see that what they are studying is important and topical, and can help you think more clearly about all the major topics on any given day....

You'll hopefully learn, if you haven't already, about something called Keynesian economics, named after John Maynard Keynes, a British economist who wrote most famously between the two World Wars. His ideas were controversial as they went again the grain of classical economic thinking, the thinking most prevalent at the time; that of balanced budgets, and allowing the forces of the market to do their work, waiting for the long run to see that all was well.

Keynes made a fairly simple point, notably that there may just be situations where the economy doesn't just pick up. Recall, he wrote his most famous contribution, his General Theory, during the Great Depression when the economy failed to pick up and things didn't seem at any point soon to be getting better. Classical economists would say that in the long run, the depressed demand in many markets would lead to the necessary re-adjustments (falling real wages) such that eventually, things would pick up again - in the long run. Keynes's retort, famously, was that "in the long run we're all dead".

Keynesian thought led to demand management, where governments use fiscal and monetary policy to engineer stability: To remedy the downturns and temper the boom times. It hasn't always been the flavour of the month however, and the strong monetarist counter-revolution of the late 1960s and 1970s appeared to have destroyed Keynesianism. However, a certain group of economists, of the Austrian variety aligning themselves behind Friedrich von Hayek have persistently argued against Keynes and Keynesianism. Hayek's main thesis was that man isn't capable on his own of understanding the market, nor is any government, and hence should refrain from attempting to set up mechanisms in the face of the market; such attempts are doomed to fail.

Such Austrian economists are prolific bloggers, and hence you can read their thoughts at Cafe Hayek and EconLog perhaps most vociferously. Today in the US (and Canada) it's Labour Day, and hence it was predictable that at these blogs, something would be posted in the ilk of responding to Keynesian economics, which is percieved by Austrians to have been particularly sympathetic to workers.

Hence, Don Boudreaux, who has a habit of posting the letters he's written to just about everyone who happened to utter anything he disagreed with, writes and posts on Cafe Hayek, his letter regarding what good Keynes apparently brough humanity. It's an interesting read, and I would encourage you to read the blogs of Austrians because they will challenge you to substantiate the things you believe and are taught in what is a Keynes dominated profession, much to the dislike of Austrians.

What you will find as you study economics is that views you previously held that were away from the centre ground, so to speak, will be challenged, and I doubt you'll be able to keep to them. For example, strong views regarding minimum wages I doubt you'll keep once you're done your degree. Equally, if you enter with strong right-wing views which may border on the Austrian, I think you'll also be challenged away from them.

The fundamental assertion of Austrians is that the market knows best, the market does best. You'll learn about the Fundamental Theorems of Welfare Economics, and hence you will learn that the market is an effective tool for communicating the most information to the most people - provided a set of assumptions hold.

Now, the last bit is important, because it's something that the writers at EconLog and Cafe Hayek choose to ignore because it doesn't suit their prior dispositions regarding the economy. Boudreaux has at times compared the healthcare and education markets to the market for buying pet food, for example. However, as you will learn if you study Contemporary Issues in the UK Economy in your second year, and also via microeconomics, the market is only effective if the price mechanism works. It breaks down when information is imperfect.

The important thing though again that you will learn when studying economics is that the knee-jerk reaction towards governments running everything where the market fails is another mistake to make - it's one made by thost on the left usually. It may well be the case that a failure in the market due to imperfect information of some sort or another cannot be remedied by government, and the government will only make the situation worse. The market for rail travel may be an example; all the assumptions of perfectly functioning markets are not upheld, but it doesn't mean that the government will run the railways better than the private sector.

However, health is dramatically different to pet food. Buying the wrong pet food may lead to an unhappy dog for a day or so; the mistake is easily rectified. Buying the wrong healthcare treatment from the wrong healthcare provider may well not be so easy to rectify. Information is not so readily available to all market participants, and hence you see that working from principles of information we can conclude that healthcare is not likely a market best left to market forces - regardless of your prior prejudices in this area. Now, the solution will not necessarily be a full blown NHS, but it also won't be a fully free market.

The bottom line to this post is this: Boudreaux, the writer of the blog post linked up earlier, takes a position on the fringes of the economics profession, and in order to do that, he has to ignore much evidence contrary to what he originally believes. He has to ignore all the above regarding information in health markets and other such markets. But on the other hand, he's just as wrong as the person who believes only the government should be running most (if not all) things - both must ignore basic economic theory to justify their position. Hopefully by the end of your three years, you'll take neither position, and you'll be able to reason and justify all the things you believe about the economy, hence when you read people like Boudreaux, you can understand why he's wrong.

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Oxford Economics Dictionary Online

As I mentioned in the revision lecture on Tuesday, getting yourself an economics dictionary will be really useful for you in getting short and sharp definitions for the concepts you're talking about in any essay question. I just noticed that you can find the Oxford Economics Dictionary online at http://www.enotes.com/econ-encyclopedia/.

Start Your Own Blog!

Why not start your own blog? This may seem like an odd and daunting idea, or it may really attract your attention. Why would you want to start your own blog? One really great thing is that it really helps you to learn about things and make sense of them in your head - if you're going to write about them, and have people read what you write, then you need to have things clear!

Blogs are free to start - Blogger, what I use for this blog, is free and provided by Google, hence if you have a Google Account, it's straightforward to set up a blog. Another alternative is Wordpress, which again is free. You simply sign up, give your blog a name and you're ready to go.

If you do so, or if you already have a blog and you're a keen reader of this blog (and/or currently on econ101ab), let me know - I'd be delighted to follow your blogs...

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

GDP Growth and Revision Lecture

This morning, it's been announced that GDP growth in 2011Q1 was 0.5%, which essentially matches the contraction of 2010Q4, and is, according to Duncan Weldon, a borderline terrible growth figure.

On another note, next Tuesday is the econ101b revision lecture. Come along with questions, we have two hours to play with. It's 3-5pm in Mech Eng G31.

Monday, April 11, 2011

The Vickers Report - Interim

The Independent Commission on Banking, being headed up by Sir John Vickers, is delivering its interim report today. The commission is due to report back in full by September, but as is the way, in the meantime it's giving us some titbits to go on. You can see some comment here from FT Alphaville - they'll be commenting more later.

If you are interested in the Financial Crisis and its aftermath, and interested in what will happen to the banks (who isn't?), and want to be somewhat informed, then having a read of all this will help you. It will certainly help you as you revise and think about what we talked about in week 7 on Money and Interest Rates, and also as you think about money markets more generally (feeding into the LM curve in the IS-LM model).

Highly recommended stuff...

Friday, April 8, 2011

A Little Bit of Looking at the Data

Today the Daily Mail is again talking about how the UK was on the edge of an economic apocalypse before George Osborne saved the day! Some things never change.

What would be more interesting would be to actually look at the economic data beneath the political and journalistic hyperbole, wouldn't it?

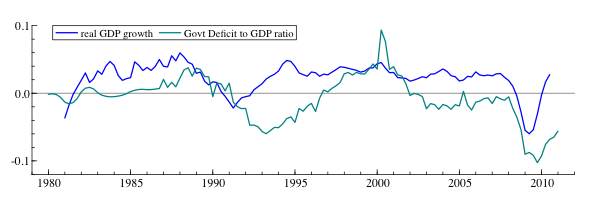

I'm writing up some long overdue notes for some lectures I did on fiscal policy, and I figured I'd just have a little look at the government deficit in the context of real GDP growth in the UK over the past 30 years. Here's what the two data series look like:

Why am I doing this? Well because when an economy enters a recession, things economists call automatic stabilisers kick in: Benefits are paid to people made unemployed, and income and corporation tax receipts fall since less profits are made and less income is earned. These two effects will make a budget deficit worse regardless of how profligate a government is, so long as it provides unemployment benefits, and runs an income and corporation tax system.

So what about the biggest recession in 70 years kicking in? Surely that's going to have quite an impact on government finances, right? Looking at the two series above, we can see that indeed the recession we just emerged from was deeper than anything since 1980, and indeed the government deficit was also deeper. It's interesting to note the 1992 recession, post-ERM. After that, there is quite a large budget deficit for quite a while. Interestingly enough, that deficit only becomes a surplus after 1997.

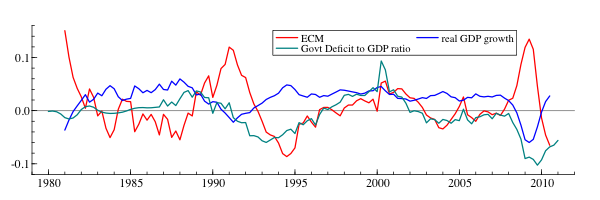

However, we should really think about taking the data seriously, shouldn't we? Eyeballing only gets one so far. Now both series are probably stationary (econometric speak), but clearly show persistence - GDP growth is strong for a while, then weak, deficits tend to hang around like bad stains. So we should think about a dynamic econometric model. The real beauty of such models (say, an Autoregressive Distributed Lag model) is that we can let the data tell us about the long run solution, or error correction reformulation as it's called in the linked paper. This is the long-run relationship between the two variables: So if real GDP growth is at its expected value, what do we expect the deficit to be?

This way we can say: How far out of equilibrium are we right now, compared to economic history? I'm not going to bore anyone with the details (email me if you'd like them, I'm more than delighted to provide), but of course it's fascinating to look at something like this and see just how much we are currently teetering on the brink. The red line in the following diagram shows us exactly how far out of equilibrium we are currently:

The deficit and real GDP growth are also plotted there still. The red line is equilibrium, or how much too high or too low is the deficit given the state of the economy. The important thing is that this is estimated over real data, and it should also be said that this is data starting in 1981, so 16 years of a Conservative government then followed by 13 years of Labour - it's a nice mix of the two.

So we see the impact of the financial crisis with a big positive movement which looks bad, right? That is until you realise that this is saying that the deficit was not large enough given the size of the contraction in real GDP! Calculations, based on the data, says that at the height of the recession, when real GDP contracted at 6%, the correct deficit given past UK economic history (16 years of Conservatives), excluding all economic theories, the deficit should have been an eye-watering 22% of GDP, not the trifling 9% it was at this point (2009Q2). Only as we entered 2010 did the equilibrium relationship (called ECM) turn negative, suggesting the deficit is too high now, and even by 2010Q3 it had not reached the depths of disequilibrium (a deficit too high) it reached in 1994.

Interesting stuff. Are we teetering on the brink of an economic apocalypse? Were Labour reckless with public finances? Not if you consider economic data taking into account Conservative policies between 1981 and 1997, at any rate.

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

The Alternative Letter

We've recently covered monetary policy, and the current UK framework where the Bank of England has been granted independence from political interference to use tools of monetary policy (interest rates and QE amongst others) to achieve an inflation target. We noted in lectures that for a long time now, the Bank has missed the target and we have inflation over 4% (target 2%).

In Money Week there's a mock alternative response from the Chancellor; if inflation misses the target, the governor of the Bank writes a letter to the Chancellor, and the next day the Chancellor responds. The Chancellor usually refrains from being critical, and hence this has drawn criticism: Why shouldn't the Chancellor start holding the Governor to account?

The letter is of course highly sarcastic and tongue in cheek, but it is written for a reason and helps us think a little more about monetary policy and the current framework. It is essentially true that the Bank has no regulator: Nobody is really keeping check on whether the Bank hits the target or not. Osborne can't really do it, as the letter kind of hints at with its final riposte: Maybe we should find someone else to do the job if you can't Mervyn (paraphrasing). If Osborne wrote a letter like this, it would be a very clear indication that the Bank's independence was no longer. If the Bank did subsequently raise rates, regardless of why it did so, it would be easily interpreted as having done so under political pressure. And if political pressure starts once again to dictate what happens with interest rates, then we're right back to square one, where we were before 1997 and the political business cycle.

The letter also makes some other important points:

- Why are forecasts so bad?

- How do we know inflation is caused by the weak exchange rate and not negative real interest rates and QE?

On the first, the stock answer is that the economy is a complicated beast. But the letter kind of hints at that when it criticises the reliance on the output gap in a rather Austrian-type criticism: How can we really know about this incredibly complicated and generally theoretical entity called the macroeconomy? Of course, just because something is complicated is no reason to give up on it, particularly when policy needs to be made (I'm not going into any arguments over free banking and the like).

On the second, the 30% fall in the trade-weighted exchange rate noted in lectures means that the goods we import (which is quite a few) are more expensive, and since these often take up a large portion of our basket, then it is quite reasonable to assert the high inflation is due to that - along with the VAT rise, since that also makes the goods we buy more expensive. Remember, inflation is just the change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), year-on-year, for a given month, and the CPI is calculated over a "basket of goods" which is supposed to be representative of what the average person buys.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Correlation and Causality

We've now got through the course content for econ101b in lectures, so enjoy the vacation! I thought I'd link up an article by John B Taylor, who has recently become a staunch proponent of government austerity. He's supported/encouraged by Greg Mankiw, who is another Republican poster child.

For those more averse to all things US, the Republicans are much more right wing than any of the mainstream UK political parties, although their closest equivalent would be the Conservative Party.

John B. Taylor is the man who proposed the Taylor Rule, a rule that monetary policymakers should follow when setting monetary policy. He strongly believes the sole cause of the Financial Crisis was that monetary policy was too loose, according to his model (scroll through old posts on his blog and you'll get a sense of this, I can't find the original article).

In the main linked article though, Taylor takes us through some scatter plots. Now these are interesting scatter plots - they show that government purchases are positively correlated with unemployment, and that investment is negatively correlated. From this, Taylor draws the conclusion that austerity is fine and should be encouraged (since it means lower government purchases) while at the same time investment should be encouraged.

This is all well and good, but a scatter plot shows correlation and not causality. Why does this matter? Well, Taylor proposes austerity (cutting back government purchases drastically) because in his mind it will cause lower unemployment. But what if the causality is the other way? What if high unemployment causes higher government purchases? Now this is hardly controversial really, since if people become unemployed, the government will have more to do: Higher benefits, likely higher other costs too, and naturally we might see some attempt by government to stimulate the economy by increasing purchases (data is 1990 on). If this happens, the purchases happen at the same time as the unemployment exists, hence we get a correlation like in the plot.

So does Taylor's plot really tell us much? Even if the government purchases worked, this plot wouldn't tell us that since it's a dynamic picture - i.e. the reduction in unemployment wouldn't necessarily come instantaneously! So the plot has ignored causality and also the dynamic nature of cause and effect in the macroeconomy.

It's another example of why it's very hard to know who to trust when doing economics. Blogs are great - they contain the opinions of top economists who can comment on real world events as they are happening. But they are not what we call peer reviewed. For a paper to get into a journal, it must be read by a number of referees who decide on its quality. Shoddy data work like that shown in this blog post, would not get past the referees and editors at a top journal.

The conclusion to draw - be careful, and in particular if you do read blogs (and I'd recommend it!) try to read a balanced selection of them - something like the list given on the right-hand side of this blog.

Thursday, March 24, 2011

The Budget

Yesterday George Osborne gave his first full budget, and in reality it did not change a lot. There is much commentary all around, but often the best place to go to for informative and balanced comment is the Institute for Fiscal Studies. A little look at their track record over time shows they are happy to criticise whichever party is in government. Here is their take on yesterday's budget. Well recommended. And enjoy that extra penny off each litre when you fill up next...

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

Superfreakonomics in Birmingham

I'm sure publicity for this will pick up in time, these guys are not shy by any stretch of the imagination, nor do they miss a money-making promotion opportunity. Stephen Dubner is in Birmingham on 20 June promoting his book with the economist Steven Levitt, Superfreakonomics, the "freakquel" to Freakonomics.

I'm quite sure it'll be a very entertaining show and if you're interested in pursuing economics further, and you're in Birmingham in June (or Brighton, Liverpool or Cambridge), then it will be worth your while getting along!

Monday, March 14, 2011

Monetary and Fiscal Policy

This week and next week we'll talk about monetary and fiscal policy. I put up the link last week of the interview with Mervyn King, governor of the Bank of England, which contained his views on how monetary policy saved the economy from the abyss during the recession in 2008-09. Equivalently, politicians and many economists argue that fiscal policy can have an impact on growth - but that impact is complex, as we'll find out. Nonetheless, Labour have today started talking about their proposals for growth, ahead of next week's Budget.

Changes to fiscal policy (how the government spends and taxes) are bound to have an impact on the economy; you learnt in econ101a how taxing wages distorts incentives in markets, and this is the same in goods markets too. Hence governments are able to influence economic activity in dramatic ways. In econ101b we'll look a little more at this at the macro level, thinking about government spending as an aggregate and how that can influence economic activity.

Monday, March 7, 2011

Mervyn King Interview

Quite soon we'll start to look in quite a bit of detail at monetary policy. Here's an interview in the Torygraph Telegraph with the Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, which is very interesting reading.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Chancellor and Governor

Later in term we will spend some time thinking about monetary and fiscal policy; these are the two ways in which governments attempt to influence economic activity, wisely or otherwise. Both are currently in the news regularly; fiscal policy because the Coalition is running a very tight fiscal policy in order to bring down the government deficit, and monetary policy because interest rates remain essentially at zero yet inflation is high.

The current monetary policy arrangements have the Bank of England commissioned by the government to set interest rates to achieve an inflation target of 1-3%. However, for 20 of the last 30 months, that target range has been missed by the Bank. Every time the target is missed, the Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, must write a letter to the Chancellor explaining why the Bank has failed in its duty. The Chancellor usually responds, and these letters, in the interests of openness, are published on the internet. Here is George Osborne's recent response to King.

The interesting aspect of this letter is that Osborne suggests that by staying the course of the government's very tight fiscal policy, this will help monetary policy to be more effectively conducted because without it, inflation would surely happen. Of course, there are plenty of counter arguments to this assertion, not least that given inflation is generally imported inflation currently (cost push), then it will not necessarily fall due to domestic actions by governments (unless they can increase the exchange rate). Furthermore, such a contractionary fiscal policy could yet see the UK returning to a recession (we saw negative growth in the last quarter), in which case again if inflation is imported, there seems little reason why this would make the Bank's job any easier: Inflation will still be high, and the economy in a recession.

Furthermore, whatever the government does with fiscal policy, the Bank can always counteract with monetary policy: Assuming their efficacy, if fiscal policy was loose, then tight monetary policy would suffice to keep economic activity reasonably constant, and equivalently a tight fiscal policy could be counter-balanced with a loose monetary policy (so QE2 and more).

Thursday, February 10, 2011

The Bank of England's Big Decision

Later in term we'll talk quite a bit about monetary and fiscal policy and we'll start to understand just why this decision is so tough. In any state of the world it is hard to forecast and know what is going to happen in the future and hence know the right thing to do with monetary policy.

Currently the Bank has a problem in that economic growth is negative yet inflation is above its target (of 2%). In an ideal world, the Bank would have one of these two problems to deal with, because they demand conflicting responses. Negative growth demands loose monetary policy, hence low interest rates, in order to stimulate economic activity. But high inflation demands tight monetary policy, hence higher interest rates, in order to keep economic activity in check and thus keep inflation down.

There's another part of this difficult question though which the Bank must factor in: Much of our inflation is imported from abroad, as the pound has lost so much value in recent years. As we've learnt recently, if interest rates did rise here in the UK, it is possible that the exchange rate would appreciate, hence reducing that imported inflation effect.

Either way, we lie in wait for the decision, expected in about 24 minutes...

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Monetary and Fiscal Policy

In it he mentioned the problems he faces as the head of the Bank of England, which is in control of fighting inflation: He expects inflation to rise to 5% in 2011, yet the Bank's target is 2% (plus or minus 1% so a range of 1-3%). Yet GDP growth was negative in 2010Q4, and is not expected to perk up any time soon.

The problem is that high inflation would usually be met by the Bank of England with higher interest rates, yet growth is weak: And higher interest rates would hurt growth (we'll study the interest rate transmission channel from interest rates to economic activity later in term).

The fundamental problem is that of the two basic types of inflation covered yesterday, demand-pull and cost-push, the UK is suffering cost-push at the moment: The weak exchange rate imports inflation, and commodity prices are high at the moment - both factors that makes inputs more expensive.

However, as also mentioned, inflation can come simply from expectations becoming reality. If people start expecting higher inflation then they will attempt to build that into their wage settlements, particularly if and when the economy begins to recover. Then with more money in the economy, this will likely translate into higher actual inflation. So the current cost-push inflation may turn into demand-pull inflation, and this is what the Bank of England is seeking to avoid.

It seeks to avoid it precisely with speeches like this, attempting to show us that it knows what it is talking about when it comes to the economy...

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

GDP Falls!

After three quarters of positive growth, analysts had expected a small positive number for GDP growth, but numbers plummeted. There have been many concerns since the Coalition implemented its austerity package that it might plunge the UK into a double dip, and hence those worriers appear to be feeling vindicated in voicing their concerns.

However, there are good arguments for why we might have seen such a contraction: We had lousy weather for most of December! Certainly George Osborne has leapt on this explanation to maintain that austerity remains the right path to take. Construction fell particularly strongly in the period, down 3.3%, supporting this view. It's a rather British response to blame the weather, isn't it?!

Yet December was just one month out of three in the quarter. What happened in the other two months? Growth clearly couldn't have been particularly strong in that period.

Do these figures mean we're definitely heading for a double dip? Of course not. The numbers will still be revised (this is the first estimate based on just a third of the available data), although it is unlikely they will be revised up substantially enough that growth would become positive. And it's just one quarter - the working definition for a recession is two quarters of negative growth.

But it ought to be a concern. We learnt last week about the role government spending plays in aggregate demand (how much we all demand of goods in the economy), and as such it ought not to be surprising that as the government reduces G significantly, aggregate demand falls and growth slows. The government is hoping for a strong longer-term impact rather than any short-term impetus with its austerity - it argues private sector behaviour has long been crowded out by high government spending. Later in term we'll assess in more detail crowding out and we'll be better placed to give an assessment of the likely success of the Coalition's economic strategy.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Jobless Growth?

We won't be able to go too much into Globalisation, but by implication you'll learn about the economic arguments for Globalisation - along with potentially some arguments against it. It will come too late to be covered in a tutorial unfortunately so later in term I'll provide some discussion questions for you to ponder anyhow.

Nancy Folbre is an economist at the University of Massachusetts, and she has written an article in the New York Times about jobless recoveries and jobless growth.

A jobless recovery is what it says on the tin: An economic recovery (GDP is growing again), but without unemployment falling, or even employment rising. Workers in jobs are becoming more productive, it would seem, instead of more hiring taking place.

The explanation given is Globalisation. The usual dirty word. Apparently this has affected the economic incentives US companies face, meaning that while still being patriotic American companies, they are now forced to locate abroad to produce cheaper to sell the goods back to Americans. Hence the jobs producing the goods go abroad. We get cheaper prices, but not the jobs.

Of course, this very simplistic view is just that, and it ignores most if not all economic theory. It is a protectionist view. We can't really compete with these productive workers elsewhere, and moreover we don't really want to - so we erect barriers and protect ourselves - tariffs, subsidies, etc. But then we end up producing what China could produce cheaper, instead of innovating and creating better jobs producing new and better things that people want to buy (entrepreneurship), and allowing China to produce the things they have a comparative advantage in producing.

Essentially this is populist stuff: Appeal to what people want to hear now, regardless of where it will leave us in the future (substandard goods, mediocre workers molly-coddled by the government, higher prices). The truth is painful: Other countries are able to compete and produce some things America currently produces much more cheaply. It's a hassle to keep on changing and be subject to the pressures of competition. But it's healthy too, since it keeps us on the ball, producing only things that people actually want.

If you are someone prone to economic nationalism like this, it is worth asking the question: What is the difference between thinking about production here vs China, and production in the south of England vs Northern Ireland? Should we stop trading with folk in other parts of the UK? What about other parts of our city? It would be perverse. As Don Boudreaux writes:

This note is inspired by DG Lesvic’s objection to Art Carden’s use of the reductio ad absurdum – an objection that, I confess, I do not share.

Reductios work so well when arguing against proponents of economic nationalism (that is, “protectionists”) because, economically and morally speaking, there is absolutely no difference between Suzy trading with Joe her next-door neighbor and Suzy trading with Jose in Mexico, Josef in Austria, or Javu in China. None.

So when any protectionist argues, based on reason X, for restrictions on trade drawn along national political borders, it’s always enlightening to apply the same argument X to trade restrictions drawn more locally – even as locally as the individual.

Fritz Machlup said in class at NYU back in 1981 that arguments for protectionism, when followed through to their logical conclusion, always ‘prove’ that a person’s right hand should not trade with that person’s left hand.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Inflation Higher

The ONS calculates a number of price indices: Numbers that reflect the level of prices for a collection (or bundle or basket) of goods. Inflation then, according to one of these indices, is the change, year-on-year. So the number announced today was the increase in prices in December 2010 relative to December 2009. We compare year-on-year to account for seasonal patterns that might distort our understanding of what's going on in the economy. Whichever way you look at it, inflation is high.

The Bank of England is set a target of 2% for inflation, yet it was nearly 4%. This creates problems for the Bank of England because inflation is relatively high, yet GDP growth is still fairly embryonic after the recession. Any attempt to curtail inflation by the Bank of England will put downward pressure on economic growth, and hence would not be helpful.

Yet the longer inflation remains higher than target, and particularly with the VAT rise that we've just had at the start of 2011, the more it starts to get built into new wage settlements by workers. If workers are paid more, this will likely lead to higher inflation since consumers have more money to spend while supply levels haven't adjusted.

More next week...

Inflation Higher

The ONS calculates a number of price indices: Numbers that reflect the level of prices for a collection (or bundle or basket) of goods. Inflation then, according to one of these indices, is the change, year-on-year. So the number announced today was the increase in prices in December 2010 relative to December 2009. We compare year-on-year to account for seasonal patterns that might distort our understanding of what's going on in the economy. Whichever way you look at it, inflation is high.

The Bank of England is set a target of 2% for inflation, yet it was nearly 4%. This creates problems for the Bank of England because inflation is relatively high, yet GDP growth is still fairly embryonic after the recession. Any attempt to curtail inflation by the Bank of England will put downward pressure on economic growth, and hence would not be helpful.

Yet the longer inflation remains higher than target, and particularly with the VAT rise that we've just had at the start of 2011, the more it starts to get built into new wage settlements by workers. If workers are paid more, this will likely lead to higher inflation since consumers have more money to spend while supply levels haven't adjusted.

More next week...

Minimum Pricing on Alcohol

You will have learnt about market equilibrium in econ101a and hence about the impact of minimum prices or minimum wages (and maximum variants too) - they distort the market away from equilibrium reducing consumer and producer surpluses and creating a deadweight loss. Economically there isn't really an argument for them - when considering partial analysis such as this (i.e. analysing one market - that for alcolhol - in isolation).

Perhaps that's why the experts that have advised the government on this are not economists. Economists particularly of a more libertarian perspective would argue that such actions impinge on the liberty of people - why does the government know best what I should do in my drinking habits?

Economic arguments could be advanced though. It's important to try as best as possible to consider a general equilibrium analysis. The argument would be that alcohol is not necessarily a "good" in all situations - it can be what we described in the lecture yesterday as a "regrettable", or a "bad", when it leads to social unrest. Clearly alcohol-related violence and health issues will lead to additional costs for the taxpayer via policing and the NHS.

So provided you like a taxpayer-funded nationalised health service, it adds an extra dimension to such issues...

Monday, January 17, 2011

The Item Club and Interest Rates

As described by the BBC, the Item Club thinks interest rates should remain at 0.5%, where they currently are. Monetary policy is one of the tools a government has through which to manipulate economic activity; the other main tool is fiscal policy: Government spending and taxation.

Given that the Coalition government is planning to cut government spending and has already begun raising taxes via the VAT rise, economists describe fiscal policy as tight. This means that, as we will note this term in lectures, fiscal policy will restrain economic activity by contributing to a decrease in aggregate demand.

Given this, the Item Club argue that monetary policy cannot similarly be tight. A tight monetary policy would be a policy stance aimed at achieving a fall in aggregate demand. If both policies were tight, then the decrease in aggregate demand would be even stronger resulting in much slower economic growth, and potentially another recession.

Hence the Item Club rightly, in my opinion, argues that monetary policy must remain loose, and hence interest rates should remain low.

However, inflation is above the target the Bank of England is set, and hence this is why some have argued that interest rates should rise. When we get to monetary policy later in term we will get to discuss what impact interest rates have, and hence what the role of monetary policy is.

Tuesday, January 4, 2011

Macroeconomics Time

We're going to investigate a number of aspects of the macroeconomy during the coming term. The main text is Sloman, but one thing that it will be good for you to grasp is that macroeconomics is a very difficult beast to tame, and that any teacher of it will likely give a somewhat slanted (biased) view on the macroeconomy (some would even say it doesn't really exist).

So again I'll encourage you as part of your econ101b experience, and degree experience more generally, to be reading widely, and thinking through what you read, challenging what you believe and justifying it. If nothing else, it'll give you points to score when chatting with your mates...